If you take a look around at many of the retro tech websites or publications today, you’ll find that many are focused on primarily one thing: Video Games. And for good reason, our machines of yesteryear were powerhouse game machines, offering the best gaming experience of their time. But what happens if you want to do MORE than play games? If you’re like me – you enjoy a good game of Jumpman or Blue Max on your C64, or maybe you like to break out your Gateway 486 for some Duke Nukem 3D. But at some point, you have to wonder – is this all there is to life?

Sure, my fondest memories growing up was playing all of the unique game titles available on my Commodore 64, while other kids were swapping ColecoVision and Atari 2600 cartridges, but I also did more. I learned to program in BASIC, creating simple text-based adventures and rudimentary graphics. I explored the world of telecommunications through a 300-baud modem, connecting to local bulletin board systems (BBSs) and exchanging messages with other enthusiasts. I even used it for word processing, creating school reports and personal projects, long before the ubiquity of modern PCs.

I was immediately fond of the telecommunications aspect of computing. Growing up in a very rural part of southern West Virginia and having very limited to no local peers who were interested, much less understood, personal computing – being able to connect to a remote Bulletin Board System immediately connected me to others who shared my passions and interests.

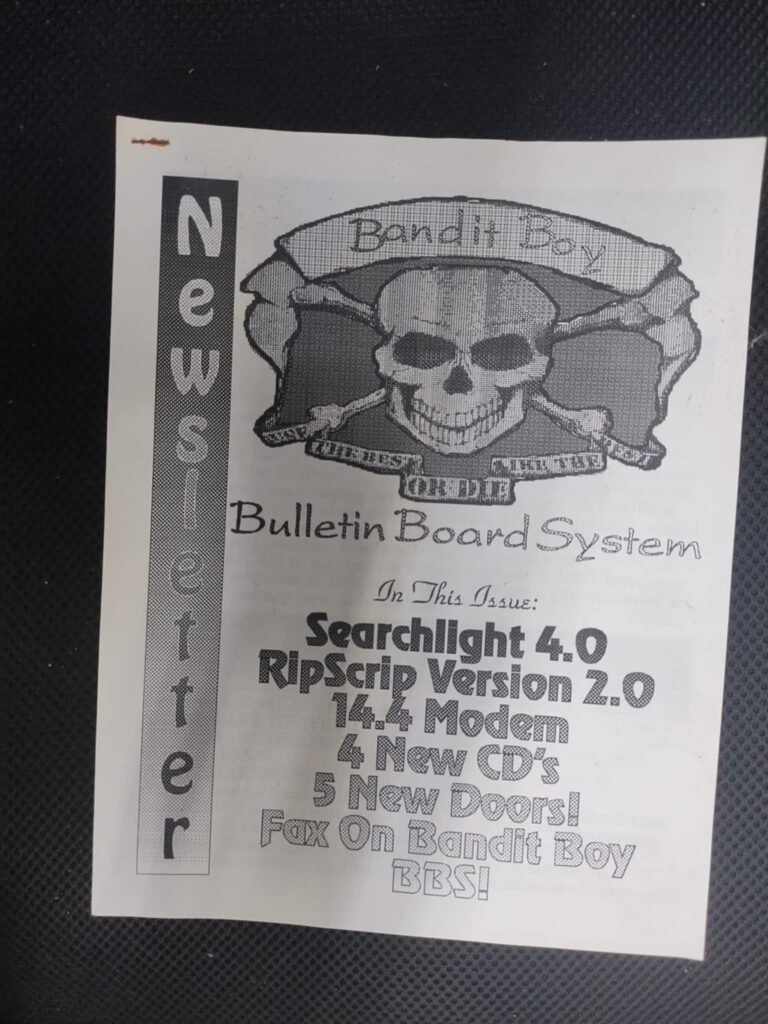

Very soon, along with my brother Dusty, I decided to open my own bulletin board system using a PC XT clone my brother Dusty brought home from an engineering office he worked at. Dusty had brought home the PC and a 1″ thick binder which was the manual for RBBS-PC, an early rudimentary Bulletin Board System written by Larry Jordan in 1982 (more info here). I was able to configure the BBS and get it up and running. I was hooked. I kept adding and expanding to the BBS – adding more and more files, graphics, and upgrading storage and speed. I would ask for things like modems and cd-rom drives for my birthday and holidays. There just wasn’t anything cooler.

Once the Internet started coming around, it was just an amazing opportunity to expand our connection to one another. Assuming you had a local access point, you could dial up the world without incurring those pesky long distance charges. Unfortunately for me being in rural West Virginia, there were NO local access points. I once ran up a long distance bill totaling close to a thousand dollars to which my parents weren’t too happy about. My brother Dusty once again had the inclination to open a local access point – so we did. We started with a very rudimentary BSDi server providing access services to a fractional T1 which ultimately expanded once services grew. No longer was I playing around with a handful of mixed 14.4 and 2400 baud modems, we had Lucent Portmasters serving up banks and banks of 56k modems – the latest in analog technology.

It made the “world feel closer to home” (I later used this slogan as the tagline for the ISP). I went on to become a systems and network engineer in my career and ultimately got into cybersecurity. It’s been a fun and interesting journey!

This multifaceted use of old technology highlights a crucial point: these machines were tools, not just toys. They were gateways to learning, creativity, and communication. The limitations imposed by their hardware and software often sparked innovation and resourcefulness. Some of the best art I have ever appreciated came from the constraints of ASCII characters and 16 colors in the form of ANSI art. Some of the best music I have ever appreciated came from the fantastic SID chip in the Commodore 64. Having these constraints sparks a level of problem-solving creativity that just doesn’t seem to happen when there are few or limited constraints. This is why I believe that modern video games just don’t seem to have the same charm as their ancestors.

Beyond games, consider the Apple II. Beyond its gaming prowess, it was instrumental in the development of desktop publishing, education, and even early music production. The Amiga, with its advanced graphics and sound capabilities, became a platform for digital art, animation, and video editing, laying the groundwork for many of the creative tools we use today. The early IBM PCs, while initially business-oriented, fostered the development of software that revolutionized industries.

Even today, this value extends beyond the historical significance. Old technology can provide a tangible connection to the past, allowing us to understand the evolution of computing and appreciate the advancements we’ve made. It can also be a source of inspiration, reminding us that innovation often arises from constraints.

For those interested in electronics and computer architecture, these machines offer a hands-on learning experience. Repairing and modifying vintage hardware provides a deeper understanding of how computers work at a fundamental level. The simplicity of older systems, compared to the complexity of modern ones, makes them ideal for experimentation and exploration.

Furthermore, there is a certain charm and aesthetic to retro tech that resonates with many. The tactile feel of a mechanical keyboard, the warm glow of a CRT monitor, and the distinctive sounds of vintage hardware create a unique sensory experience.

So, the next time you power on your old computer, remember that it’s more than just a gaming machine. It’s a piece of history, a tool for learning, and a source of inspiration. It’s a reminder that technology, at its core, is about empowering us to create, connect, and explore. And sometimes, it’s about remembering that the seeds of our digital present were planted in the code and circuits of our digital past.

Did you enjoy this article? Click here to stay informed, support retro, and subscribe to Computes Gazette today!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.